Saturday, September 30, 2006

Finally... i know how to upload!!!

Anyhow... enjoy! I have a few more full songs to upload, but i need to figure out how to cut then down first (which may/may not take about a year).

Indestructible...

Great guitar solo (even if it is badly recorded, you get the idea)...

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Sick of Politics

If

By Rudyard Kipling

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you

But make allowance for their doubting too

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise.

If you can dream–and not make dreams your master

If you can think –and not make thoughts your aim

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap by fools

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken

And stoop and build ‘em up with worn out tools

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch and toss

And lose and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after you are gone

And so hold on when there’s nothing in you

Except the will that says to them: Hold on!

If you can talk with crowds and keep our virtue

Or walk with kings, nor lose the common touch

If neither foes, nor loving friends can hurt you

If all men count with you, but none too much

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds worth of distance run

Yours is the earth and everything that is in it

And, which is more, you’ll be a man, my son.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Bit male-centric. Nonetheless nonetheless. I like.

(The formatting is gross, I know. But I can't help it!)

Monday, September 18, 2006

Subtle scholar, but what an inept politician

by Waleed Aly

September 18, 2006

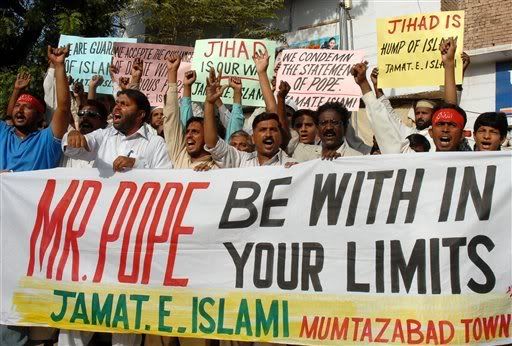

The Pope should mind his words. So should some of his Muslim critics.

LET me get this straight. Pope Benedict XVI quotes the 14th century Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Paleologus asserting before a Persian Islamic scholar that the prophet Muhammad brought nothing new to the world except things "evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached". Some Muslims clearly interpret Benedict to be quoting Manuel with approval, and take offence at the suggestion that Islam is inherently violent. The response is to bomb five churches in the West Bank, and attack the door of another in Basra. In India, angry mobs burn effigies of Pope Benedict. In Somalia, Sheikh Abu Bakr Hassan Malin urges Muslims to "hunt down" the Pope and kill him, while an armed Iraqi group threatens to carry out attacks against Rome and the Vatican.

There. That'll show them for calling us violent.

Meanwhile, other commentators seem to be vying to be most hysterical. Libya's General Instance of Religious Affairs thinks Benedict's "insult … pushes us back to the era of crusades against Muslims led by Western political and religious leaders". And a member of the ruling party in Turkey has placed Benedict "in the same category as leaders like Hitler and Mussolini", in what must surely be an insult to those who suffered under them.

Closer to home, Muslim Community Reference Group chairman Ameer Ali cautioned Benedict to "behave like (his predecessor) John Paul II, not Urban II (who launched the Crusades)", while Taj al-Din al-Hilali declared startlingly that the Pope "doesn't have the qualities or good grasp of Christian character or knowledge". It's fair to say perspective has deserted us.

Parallels with February's Danish cartoon saga are begging to be drawn. As Saudi Arabia, Iran, Libya and Syria did with Denmark, Morocco has now withdrawn its ambassador from the Vatican. Egypt and Turkey called for an apology. Indeed, one expert has suggested Morocco's

decision may have been a tactic to prevent a wave of street protests similar to those that stunned the world in February. There is an awful sense of history repeating: a provocative gesture triggers an overblown response of surreal imbecility.

But this is not the same as the Danish catastrophe. On that occasion, the cartoons' publication was an act calculated specifically to offend Muslim sensibilities. The reaction was irredeemably contemptible, but the sense of offence was justified.

Pope Benedict's speech was an academic address at a German university on an esoteric theological theme that had nothing to do with affronting Muslims. The apparently offending remarks were almost a footnote to the discussion. The contrast is manifestly stark.

But it seems some elements in the Muslim world are looking avidly for something to offend them. Meanwhile, governments looking to boost their Islamic credentials are only too happy to seize on this, or nurture it, for their own political advantage. At some point, the Muslim world has to gain control of itself. Presently, its most vocal elements are so disastrously reactionary, and therefore so easily manipulable.

Here, the vociferous protests came from people who, quite clearly, have not bothered to read Benedict's speech. Worse, some (like al-Hilali and Ameer Ali) themselves regularly complain of being quoted incorrectly and out of context. Had such critics done their homework, they would have noted Benedict's description of Manuel II's "startling brusqueness". Manuel's point was that violent doctrine could not come from God because missionary violence is contrary to rationality. Benedict's point was a subtle one: that Manuel draws a positive link between religious truth and reason. This was the central theme of the Pope's address. He was silent on Manuel's attitude to Islam because it was beside the point he was making. Clearly, Manuel II was not a fan of the prophet Muhammad. But that does not mean Benedict isn't either.

The trouble with being the Pope is that you are simultaneously a theologian and a politician. Theological discourse is regularly nuanced and esoteric. Political discourse

is not. Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan said "the Pope spoke like a politician rather than as a man of religion", but the truth is the exact opposite. In theological terms, Benedict chose an example well suited to his narrow argument.

In political terms, his choice was poor. He was naive not to recognise how offensively it would translate into the crudeness of the public conversation, and should at least have made clear that he was not endorsing Manuel II's words.

I happen to think Manuel had a shoddy grasp of Islamic theology. Indeed, the Islamic tradition would have much to contribute to the theme of Benedict's lecture. While medieval Christendom fought science stridently, the relationship between faith and reason in traditional Islam was highly convivial.

That's why I would be interested to have heard how the Persian scholar responded to Manuel's argument. I'm fairly certain, though, he wouldn't have called on Muslim hordes to hunt down Manuel and kill him.

Waleed Aly is an Islamic Council of Victoria director.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

The poisonous political cycle that harms us all

There is something frightening about two sides fighting a war each claims the other started., writes Waleed Aly.

ON THE first anniversary of the September 11 attacks, Britain's most vile terror-loving organisation, al-Muhajiroun, held a celebratory conference. Members gathered to recall how "magnificently" the twin towers were reduced to rubble.

Conference excerpts were replayed on radio after the London bombings last year. A spokesman said it was perfectly acceptable in Islam to kill civilians. Naturally, this sickened me as a person and insulted me as a Muslim. But it did not disturb me as much as I expected: his ranting was so maniacal it didn't quite seem real.

But then he said something that jolted me rudely back to reality. Islam does not permit one to start wars, he said, but September 11 was not the start. It was a response to decades of aggression. He insisted that he didn't start this war, but he was intent on supporting those who would finish it.

This statement was so disturbing because it was so familiar. It is precisely what we hear from our political leaders every time a terrorist atrocity occurs, precisely the sort of justification put forth before, and relentlessly repeated since, the disaster of Iraq. There is something frightening about two sides fighting a war each claims the other started, and each claims it now must finish.

Initial Western political responses to September 11 were staggeringly reductionist, triumphalist, even self-congratulatory. George Bush spoke like a comic book superhero by framing the world in terms of good and evil. Western societies were terror targets because they were so thoroughly good. We are despised because we are so virtuous.

In fairness, these responses are understandable in the emotional whirlwinds of tragedy. They give reassurance at a time of raw pain. But eventually, they must give way to more introspective nuance. And indeed, here, the Australian Government should be given credit: it has belatedly incorporated job, recreation and education initiatives into its security strategy, which at least shows a recognition that terrorism has important social dimensions.

But still, five years on, Western governments have, at least publicly, exhibited a stubborn blind spot when it comes to the impact of their own foreign policy. They have held fast to the implausible proposition that however many innocent people we kill as "collateral damage", whether by invasion, or as was the case earlier in Iraq, via sanctions that saw 500,000 children die, this in no way aids the terrorists' cause.

This ignores that Western foreign policy has always been a central plank in terrorists' discourse. Typical were the words of al-Qaeda spokesman Sulayman Abu Ghaith following the September 11 attacks: "The number killed in the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon … is only a tiny number of those killed in Palestine, Somalia, the Sudan, the Philippines, Bosnia, Kashmir, Chechnya and Afghanistan. We have not yet arrived at equivalency with them; thus we have the right to kill 4 million Americans, among them 1 million children." Morally repugnant indeed. Historically nonsensical. But driven by vengeance for suffering perceived to be inflicted by, or through, the West. The 9/11 Commission Report in the US explained as much. Western polities choose to ignore it.

Thus, the circle of blame completes itself. If terrorist ideologues are so concerned about oppression of Muslims, they might begin with the fact that most of their victims have been Muslims. They might turn attention to Sudan, where Muslims are killing and raping each other in numbers that make all else fade into insignificance. Yet until Western forces intervene, this slaughter is of little consequence to terrorists. Apparently, what matters is not who is killed, but who does the killing. So much for being vanguards of justice.

This deep terrorist hypocrisy does reveal a strong ideological element. But our politicians' tendency to pretend that past colonisation of Muslim lands and the present invasion and occupation of Iraq is irrelevant, is wilfully oblivious to the obvious. The Australian public intuit this. Well over two years ago, an opinion poll found two-thirds thought our role in Iraq would make a terrorist attack here more likely. And that was before Iraq's descent into radicalising catastrophe. It seems public wisdom trumps political rhetoric.

Five years after it all began, can we please end the poisonous political cycle? Can we admit the damage we have done and still do in the Muslim world? Can we realise that while this can never justify terrorism, it aids terrorist recruitment? Can Muslims admit that terrorism does not restore balance or return honour, but inflicts continuing oppression on innocent Muslims? I suspect, deep down, we all recognise these contradictions, but cannot find the political courage to admit them. How catastrophic that humanity uses the suffering of innocents not to reflect inwardly but to rage outwardly, to justify its next moral transgression. What an insult to those slaughtered. What a disaster for all of us if history repeats.

Waleed Aly is an Islamic Council of Victoria director.